Mathieu and Tapié, 1948–1958: A Decade of Adventure

Everything has to be reconstructed

It was just after the war, the era of liberation and reconstruction that extended to pictorial representation, when Georges Mathieu and Michel Tapié worked in concert towards the recognition of a new art form. Although dressed up in a number of different terminologies according to the promoter – ‘lyrical abstraction’,[i] ‘informel’, ‘art autre’, ‘tachism’ – it could be defined as a common will to redefine varieties of the possible beyond the frontiers already explored by cubism, surrealism, and geometric abstractivism, far from all determinism or formalism. Although the collaboration between Mathieu and Tapié did not start until 1948, it is in the previous year that the premises of this audacious project are to be found.

Georges Mathieu came out thunderstruck and overwhelmed from the historic exhibition of forty paintings by Wols[ii] that opened on 23 May 1947 at the René Drouin Gallery: ‘Wols has pulverised everything. […] After Wols, everything[iii] has to be reconstructed.’[iv] When he takes part in the second Salon des Réalités Nouvelles, where he shows three canvases executed on the floor,[v] and then at the fourteenth Salon des Surindépendants, to which he submits two canvases,[vi] Mathieu receives encouragement from the art critic Jean José Marchand, who finds the canvases ‘very lyrical, extremely moving.’[vii]

‘L’Imaginaire’, first combat exhibition for lyrical abstraction

It is in this context of artistic shock and the beginning of critical recognition that Mathieu throws himself ardently into the execution of his project, which is to ‘bring together everything that [he] considers as constituting that which is the most alive and show the works together in an exhibition […] revealing how and why this form of painting which is emerging has nothing to do with what continues to be exhibited as contemporary’.[viii] With Camille Bryen, he presents this project to Éva Philippe, the director of the Galerie du Luxembourg. They invite her to exhibit, alongside their own works, those of Hans Hartung, Jean-Michel Atlan, Wols, Jean Arp, Jean-Paul Riopelle, and Fernand Leduc. The exhibition opens on 16 December 1947 with the title ‘L’Imaginaire’. In his introduction, Jean José Marchand uses the expression ‘lyrical abstractivism’ and concludes: ‘As of now, the way is open. It’s up to the painters to show us how they use this liberty.’ The starting signal for lyrical abstraction has been sounded.[ix]

‘H.W.P.S.M.T.B.’

It is now 1948 and, having newly taken on board the role of spearhead, Georges Mathieu accepts Colette Allendy’s proposal to organise a new collective exhibition in her gallery. He decides to add to this the sculptures of François Stahly and Michel Tapié, saying of the latter that they have the great merit of ‘furiously displeasing Charles Estienne’,[x] whose rival Tapié will become within the extremely closed circle of French art critics. The exhibition ‘H.W.P.S.M.T.B.’ brings together Hartung, Wols, Picabia, Stahly, Mathieu, Tapié, and Bryen. Several of them write pieces for the catalogue, which thus becomes a multiple manifesto. Mathieu’s contribution bears the title ‘Freedom is emptiness’ and concludes with a concerted freedom of different forms of expression. Tapié for his part argues for combining creative freedom with the present, the ‘day-to-day’, staying away from any form of automatism.

After this exhibition, and as their friendship grows, Tapié and Mathieu make common cause in a distribution of roles that will see Mathieu concentrating on being an artist and Tapié on being an art critic, relying on Mathieu’s works and renown in order to consolidate his critical vision.

‘White and Black’

In July, the exhibition ‘White and Black’ opens at the Galerie des Deux Îles, recently set up by Florence Bank[xi] and showing monochrome drawings, prints, and lithographs by Arp, Bryen, Fautrier, Germain, Hartung, Mathieu, Picabia, Tapié, Ubac, and Wols. Mathieu asks the art critic Édouard Jaguer for a text and also Tapié, whose last contribution as an artist this will be. In it, Tapié sings the praises of a creative freedom freed from the straitjacket of notions of style and composition, and introduces the concept of ‘informe’,[xii] which he will later develop under the name ‘informel’.[xiii]

Mathieu is aware that while ‘at this point at the end of 1948, manifestations of pure combat have taken place, this does not mean decisive victory’.[xiv] From this moment on, he implicitly passes the baton to Tapié, not without a little apprehension as to the misunderstandings that might ensue: ‘Aware of having accomplished my role, of having done everything that was within my power to do, I know that time is on my side, that the truth will explode one day, that this free Abstraction will inevitably triumph, and I can also foresee that it may well give rise to the greatest of confusions, the greatest of banalities.’

René Drouin Gallery, Mathieu’s first one-man show in Paris

It is in May 1950, at the René Drouin Gallery, where Tapié is now artistic adviser, that Mathieu gets his first solo exhibition in Paris.[xv] This occasion sees the publication in a very limited edition of a poem by Emmanuel Looten, La Complainte sauvage, which is ‘embellished with signs by Georges Mathieu’ juxtaposed on the text.[xvi] In his text entitled ‘Dégagement’, Tapié claims that ‘trusting a Man is to present him with a risk to run.’[xvii] Mathieu will also go on to develop the theme of the aesthetic of risk.[xviii]

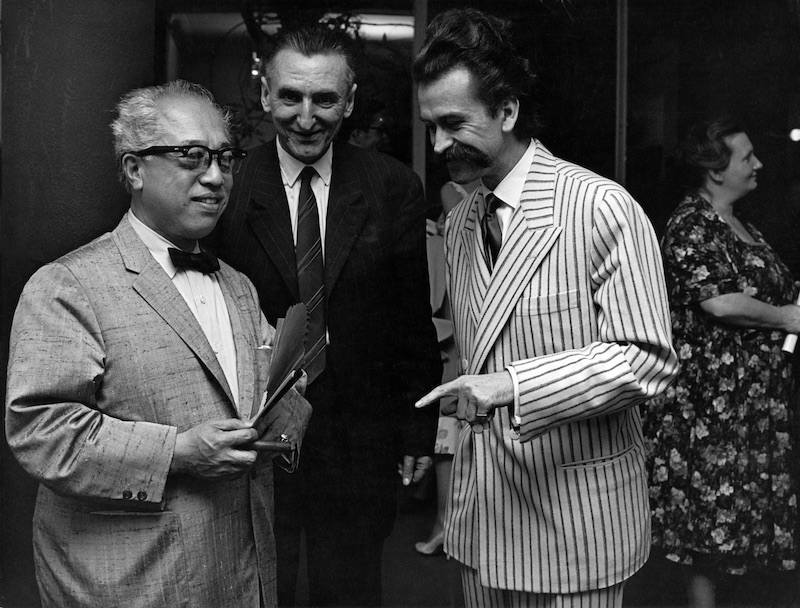

From left to right: Emmanuel Looten, Michel Tapié (holding a copy of La Complainte sauvage), and Georges Mathieu, below Flamence rouge (1950, entitled Flamence noire in the exhibition catalogue).

‘Véhémences confrontées’, the first bridge between Europe and the United States

Mathieu, who since 1947 has been public relations manager for the transatlantic shipping company United States Line,[xix] is aware of ‘concomitant research’ being carried out in the United States, notably by Pollock, de Kooning, and Tobey,[xx] at this point unknown in Europe, and seeks to defend them in Paris in November 1948 at the Galerie du Montparnasse.[xxi] Because of difficulties in obtaining all the works wanted,[xxii] this project will in the end come to fruition[xxiii] at the Nina Dausset Gallery, after Tapié has suggested that Mathieu organise with him a new Parisiano–Americano confrontation.

This historic exhibition is entitled ‘Véhémences confrontées’ as a reference to the terms ‘véhémentes’ and ‘soufrées’ used by André Malraux when Tapié first introduced him to Mathieu’s work at the René Drouin Gallery.[xxiv] It brought together works by Bryen, Capogrossi, de Kooning, Hartung, Mathieu, Pollock, Riopelle, Russell, and Wols.

In the large ‘poster-manifesto’ that took the place of a catalogue, Tapié talks about ‘informel’, opening the door for a theoretical schism with Mathieu, whose signs are incompatible with the concept of ‘informel’.

The portrait of Tapié according to Mathieu

For the exhibition ‘Véhémences confrontées’, Mathieu publishes in the English-language magazine Paris News Post[xxv] a portrait of Michel Tapié which begins: ‘It is extremely rare to come across a human being who possesses the curiously assorted characteristics of logic, mysticism, and Dadaism.’[xxvi]

Mathieu,[xxvii] a keen historian, describes a Tapié ‘crushed by a past over-burdened by tradition, religion, and glorious feats (his ancestors commanded one of the four feudal armies of the first crusade) [who] could only have a predominant attitude of refusal: refusal of action by nature, refusal of work by habit, refusal of proof by education, refusal of coherence, or at least of unity, by contagion.’

This ‘cynic of dilettantism’ astonishes and seduces Mathieu by ‘his extraordinary capacity for investigation and osmosis in the domains of the number, the world of sound and the world of the visual’. Reciprocally, Tapié holds Mathieu in high esteem, writing to him in the same year: ‘The cries of silent people of your kind are for me always of the greatest interest.’[xxviii]

Homage au maréchal de Turenne: action-painting on show for the first time

In 1951, on the closing down of the René Drouin Gallery, Place Vendôme, Mathieu introduces Tapié to the photographer Paul Facchetti whom he has known since 1948[xxix] and whom he ‘strongly urges to open an art gallery’. So Facchetti employs Tapié as artistic adviser for his gallery, the ‘Studio Facchetti’, which opens in October. In November, the collective exhibition ‘Signifiants de l’informel’, initiated by Tapié, opens. Represented are Dubuffet, Fautrier, Mathieu, Michaux, Riopelle, and Serpan.

In January 1952 Tapié organises, still at the Studio Facchetti, a new Mathieu solo exhibition entitled ‘Le message signifiant de Georges Mathieu’. Of the five works exhibited, two make direct reference to Tapié: Hommage hérétique (1951, dedicated to Michel Tapié) in reference to his Cathar origins, and perhaps also to his opinions on the ‘informel’; and Hommage à Machiavel (1952), Mathieu having used the expression ‘lucid Machiavellianism’ to refer to him.

Tapié begins the exhibition catalogue with this appreciation: ‘To arrive at “style” while avoiding all the academic traps is not the least of the stupefactions that we experience when confronted with the works of Georges Mathieu,’ and concludes that Mathieu ‘allows himself what can be seen as the most perilous challenge of the present age: elegance’.

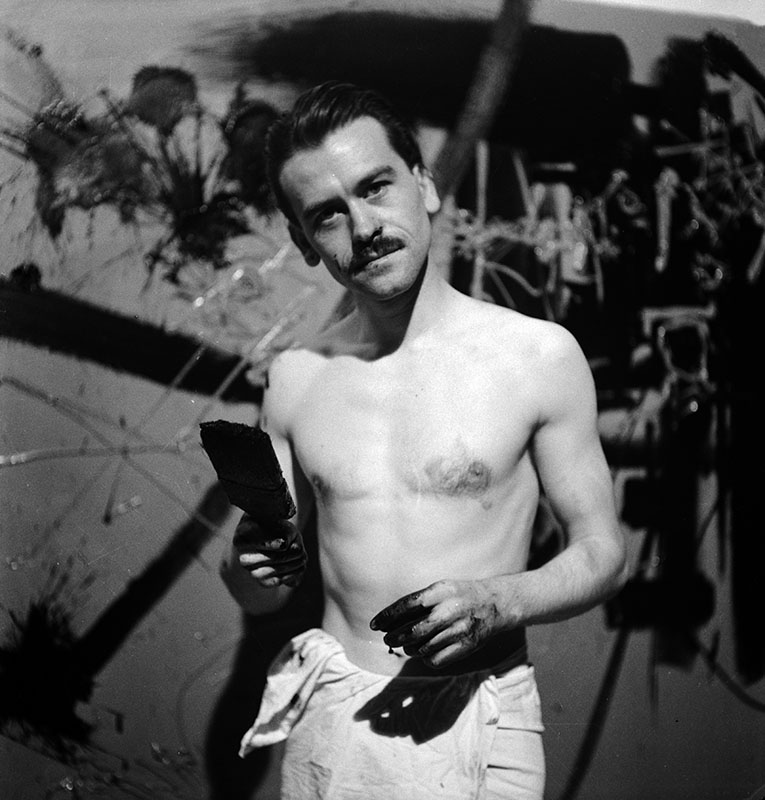

By having himself photographed on 19 January 1952, on the evening before the private viewing, while he was executing the famous Hommage au Maréchal de Turenne[xxx] at the gallery, Georges Mathieu becomes ‘the first to perform action-painting live’,[xxxi] enabling Facchetti to immortalise ‘one of the first ever happenings’.[xxxii]

The exhibition is reprised the same year at the Stable Gallery in New York by Alexander Iolas. This first solo exhibition by Mathieu in New York, entitled ‘The Significant Message of Georges Mathieu’, will lead the New York Times[xxxiii] to say that ‘Mathieu is a virtuoso of the paintbrush’.

Un art autre

In December 1952, Michel Tapié publishes a book-cum-manifesto entitled Un art autre,[xxxiv]which will be accompanied by an exhibition at the Studio Facchetti. In this landmark of art history, Tapié gives pride of place to the ‘lucid Georges Mathieu’,[xxxv] six of whose canvases are reproduced[xxxvi] alongside Pollock, Sam Francis, Dubuffet, Soulages, Hartung, Wols, Michaux, Riopelle, Fautrier, and Appel. The ‘informel’, which Tapié often defines in a convoluted fashion in the lyrical, mystical rhetoric he affects, is supplemented by the less rigid but equally sibylline concept of an ‘art autre’, extended, according to Mathieu, to a ‘mix of surrealists, expressionists, abstracts, figuratives.’[xxxvii]

La Bataille de Bouvines

On 25 April 1954 Georges Mathieu paints his emblematic Bataille de Bouvines,[xxxviii] a monumental canvas measuring 2.5 by 6 metres, in the presence of Michel Tapié and Emmanuel Looten and under the lens of Robert Descharnes’s camera. Thus does Mathieu move from photograph to film in the documentation of his work. Tapié describes the birth of this ‘key work’ in a brochure entitled 1214 illustrated with images taken from Descharnes’s film, and also in a four-page publication in English in February 1955 in the American review ARTnews under the tile Mathieu Paints a Picture.[xxxix]

Les Capétiens partout!

In 1954 Michel Tapié leaves the Studio Facchetti to look after, until 1956, Jean Larcade’s Rive Droite Gallery, where he obtains ‘the role of adviser, promoter, discoverer, and defender of living art’.[xl]

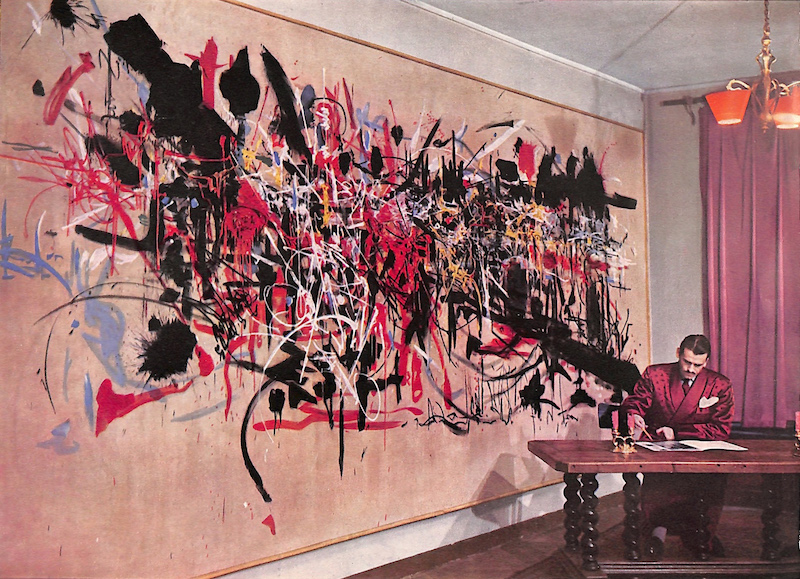

On 10 October 1954 Mathieu executes in the space of an hour and twenty minutes his celebrated painting Les Capétiens partout![xli] in the grounds of the château belonging to Jean Larcade’s father at Saint-Germain-en-Laye, in the presence of the reporters Gabrielle Smith and Dmitri Kessel from the American magazine Life.

Three weeks later this magisterial work is transported to the Rive Droite Gallery, which proposes a solo exhibition of the same name during the month of November. The exhibition catalogue includes texts by Michel Tapié, the philosopher Stéphane Lupasco, and the American painter Mark Tobey. Tapié considers Mathieu to be one of ‘the few Individuals worthy of this name in the adventure of this art autre’.

Jean Larcade, impressed by Mathieu’s courage and seriousness,[xlii] will give the Capétiens partout! to the Musée National d’Art Moderne[xliii] in 1956. This will be Mathieu’s first work to be owned by a French museum, several years after the acquisitions of the Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro; the Art Institute of Chicago; and the Solomon Guggenheim Foundation in New York.[xliv]

Le Couronnement de Charlemagne

In May 1956 the Rive Droite Gallery puts on a new Mathieu solo exhibition. In exhibiting his recent canvases ‘under Carolingian canopies’[xlv] while playing in costume the role of Charlemagne in a short by Robert Descharnes entitled Couronnement de Charlemagne in which Michel Tapié takes part, Mathieu seeks to ‘reintroduce the notion of play into art and culture’,[xlvi] and this only ‘in the presentation and not in the execution of works’.

From left to right: Prince Igor Troubetzkoy dressed up as Haroun al-Rachid, Georges Mathieu as Charlemagne, Michel Tapié as the Count of Rouergue, and Alain Bosquet as an astrologer, in front of the canvas entitled Couronnement de l’empereur Charlemagne par le pape Léon III, in the film by Robert Descharnes, 1956.

In the same year appears in English the publication in homage to Michel Tapié entitled Observations of Michel Tapié[xlvii] edited by Paul and Esther Jenkins.[xlviii] Mathieu closes it with a biographical note on Tapié: ‘His activity during the last ten years reveals itself as of major importance. […] Michel Tapié will have had the great merit of venturing into this domain with extraordinary capacities of investigation and lightning insight.’[xlix]

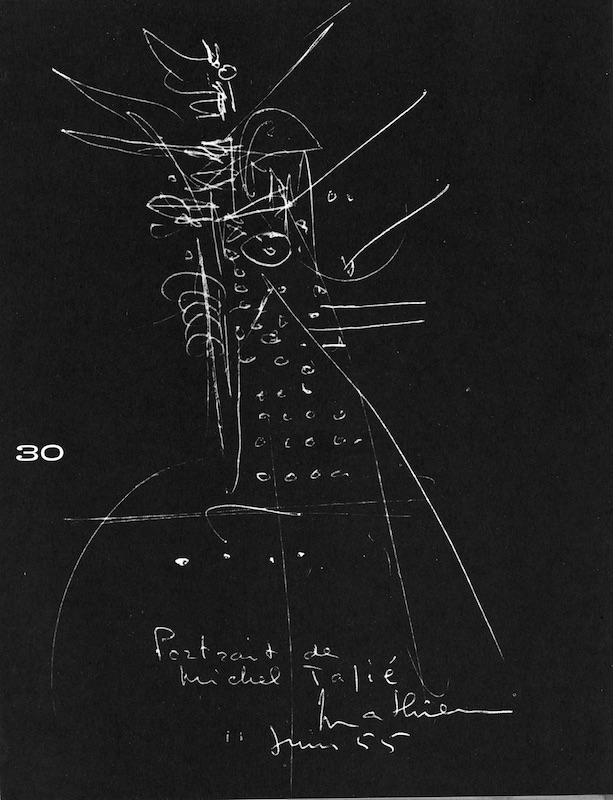

Portrait of Michel Tapié by Georges Mathieu, 11 June 1955, in Observations of Michel Tapié, edited by Paul and Esther Jenkins, published by George Wittenborn, 1956.

The ‘informel’ in Japan, the encounter with Gutai

From 1955 Tapié is working for the gallery owned by Rodolphe Stadler, who is impressed ‘as much by his extravagant culture […] as by his enthusiasm’.[l]

In November 1956 the Japanese magazine Asahi organises in the department store Takashimaya[li] the contemporary art exhibition ‘Sekai konnichi no bijutsuten’ (Contemporary world art exhibition), which will be the first to show ‘informel’ art in Japan via seventeen works from Tapié’s personal collection.[lii] The works of Georges Mathieu, Jean Dubuffet, Jean Fautrier, Sam Francis, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Tobey attract the most interest.[liii]

Tapié plans to get to know the Japanese avant-garde movement Gutai,[liv] inspired by Dada, which he wants to see join the ranks of ‘art informel’, as soon as he sets foot in Japan for the first time.[lv] Yoshihara, the founder and theoretician of the movement, has written the previous year in the manifesto of Gutai art[lvi] that the members of Gutai have ‘the greatest respect for Pollock and Mathieu because their works reveal the howl of matter, the screams of pigments and varnishes’. Mathieu’s exhibition project in Japan in 1957 gives Tapié the opportunity to go there.[lvii]

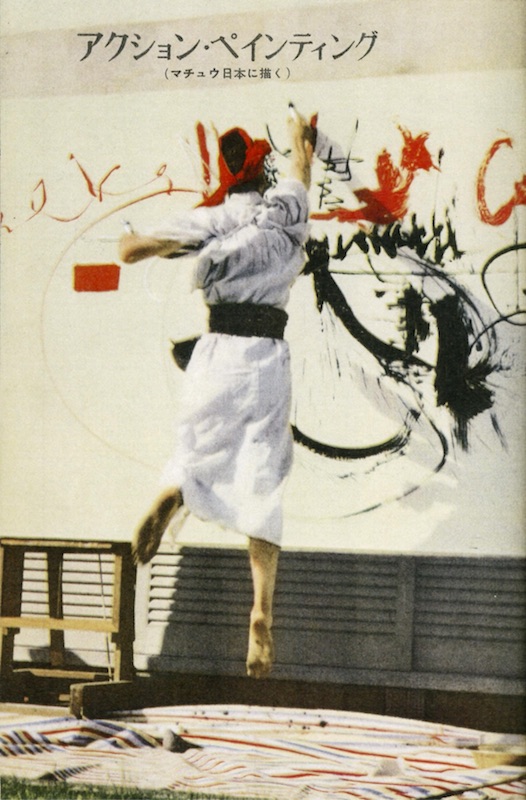

Mathieu arrives in Tokyo on 29 August and executes ‘twenty-one canvases in three days’,[lviii]watched by a number of journalists, including the spectacular Bataille de Hakata,[lix] which measures 2 by 8 metres and was completed in 110 minutes. On the day of the opening of the exhibition in the department store Shirokiya, which between 3 and 8 September will draw ‘more than 25,000 visitors’,[lx] Mathieu executes an imposing fresco 15 metres long, the Bataille de Bun’ei,[lxi] watched by a dense audience gathered in front of the shop window.

On 5 September Mathieu goes to meet Tapié at Tokyo Airport, accompanied by the painter Toshimitsu Imai, the painter and sculptor Sōfū Teshigahara,[lxii] the surrealist painter and art critic Shūzō Takiguchi, the art critic Sōichi Tominaga,[lxiii] Yoshihara representing Gutai, and Hideo Kaītō from the daily newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun.[lxiv] Before they leave for Osaka, Mathieu and Tapié visit Teshigahara’s studio.

Georges Mathieu painting La Rentrée triomphale de Go Daïgo à Kyoto (currently in the collection of the Fondation Gandur pour l’Art), in the garden of Tarō Okamoto, Geijutsu Shinchō, vol. 8, 1957.

Georges Mathieu painting La bataille de Bun’ei, behind the window of the department store Shirokiya in Tokyo, September 1957. Photo: François René Roland

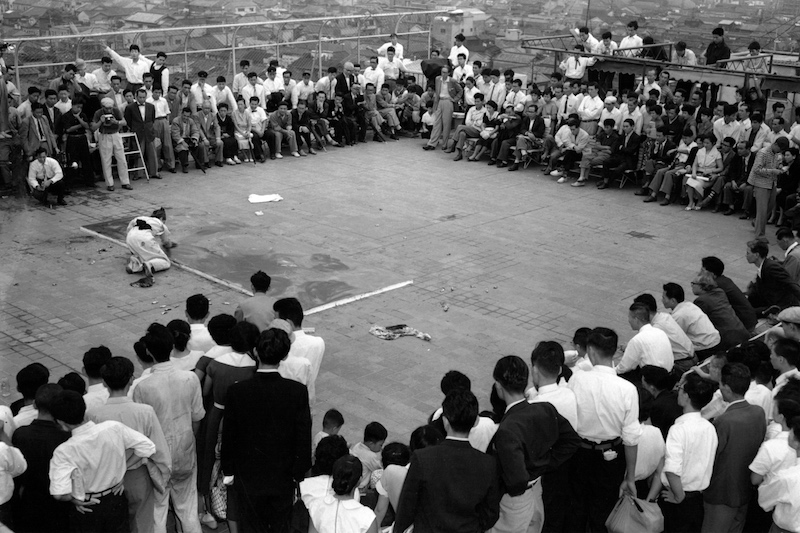

On 10 September Mathieu, Imai, and Tapié are met at Osaka station by the members of Gutai. Mathieu paints in public on 12 September ‘six canvases, one of which, Hommage au général Hideyoshi,’[lxv] measures 3 by 6 metres, on the roof of the department store Daimaru for an exhibition to take place there from 12 to 15 September, in which the canvases painted in Tokyo will also be shown.[lxvi] Then Mathieu and Tapié go to Yoshihara’s home to see the works of the Gutai artists,[lxvii] before leaving for Kyoto. Mathieu leaves Japan on 19 September, while Tapié stays on for his ‘art informel’ exhibition ‘Sekai gendai geijutsuten’ (Contemporary art in the world) at the Bridgestone Museum in Tokyo.[lxviii]

Georges Mathieu working on a painting in public, on the rooftop of the department store Daïmaru in Osaka, 12 September 1957.

This trip will have enabled Mathieu to extend his reputation to the Land of the Rising Sun, and it will turn Tapié, ‘very impressed by the overall quality’[lxix] of the work of the Gutai artists, into their defender and their official reviewer.

Sōfū Teshigahara, Michel Tapié and Georges Mathieu at the opening of the Teshigahara exhibition, October 1961 at the Stadler Gallery.

Fellow travellers of the artistic renewal

The paths of Mathieu and Tapié will end up separating for business reasons and on account of theoretical disagreements, even though their paths will cross again at the Stadler Gallery. For the duration of a decade, Georges Mathieu and Michel Tapié shared both a friendship and common interests, between the intransigent brio of the one and the elegant contradictions[lxx] of the other. Tapié’s proselytism[lxxi] in relation to Mathieu can be compared to that of the American critic Clement Greenberg in support of Pollock.

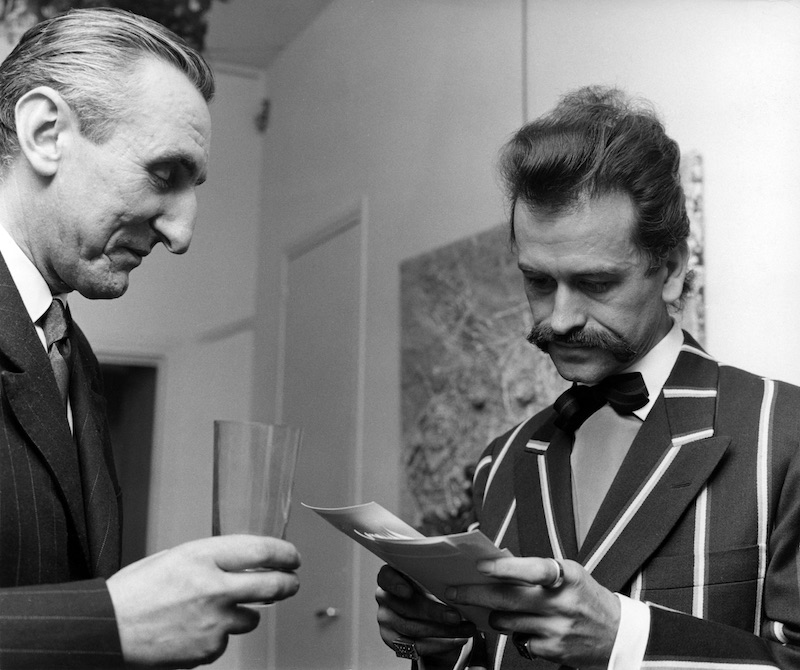

Michel Tapié and Georges Mathieu at the opening of the Lucio Fontana and Christo Coetzee exhibition, March– April 1959. Archives de la galerie Stadler

This rare painter/critic duo, operating together in a mutualist symbiosis, gave rise to a pioneering land clearing of the artistic sector, each calling upon his own methods: zealous activism in Mathieu’s case, and adventurous dilettantism in Tapié’s. They were the most effective protagonists and theoreticians in the development of free abstraction. Although this was finally supplanted in the collective imagination by abstract expressionism,[lxxii] and then transatlantic ‘pop art’, it deserves to be rediscovered today in the light of the aesthetic and conceptual variety of its pictorial production, by the yardstick ofwith regard to its avant-gardism, its international developments and it universalist ambitions, by measure of its irrefutable magnitude.

— Édouard Lombard, Director of the Georges Mathieu Committee

This essay was published in October 2018 in the exhibition catalogue “Le grand Œil de Michel Tapié”, Coedition Applicat-Prazan / Editions Skira Paris. A longer version of this essay is available in French.

[i] Also known as ‘warm abstraction’, as opposed to the ‘cold abstraction’ of the geometric school.

[ii] Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze, known as Wols (no. 27 May 1913 † 1 September 1951).

[iii] In italics in the original.

[iv] Combat, No. 1018, 16 October 1947.

[v] Survivance, Conception and Désintégration.

[vi] Exorcisme and Incantation.

[vii] Combat, 16 October 1947.

[viii] Georges Mathieu, Au-delà du tachisme, Julliard, 1963, p. 46.

[ix] Michel Tapié does not take part in the organisation of the exhibition ‘L’Imaginaire ’, nor in that of the exhibition ‘H.W.P.S.M.T.B.’, contrary to what is stated in the addendum to the reissue by Artcurial in 1994 of Michel Tapié’s 1952 book Un art autre. Moreover, Mathieu notes this in the margin of the copy of the book that is in his personal archives.

[x] Mathieu, Au-delà du tachisme, p. 52.

[xi] Subsequently called Florence Houston-Brown.

[xii] Already used in 1945 in La Voix de Paris by the conservative critic Jerzy Waldemar Jarociński, known as Waldemar-George, referring to Frédérique Villemur and Brigitte Pietrzak; in Paul Facchetti, le Studio, art informel et abstraction lyrique, Actes Sud, 2004, p. 14; by Serge Guilbaut in ‘Disdain for the Stain: Abstract Expressionism and Tachisme’ inAbstract Expressionism, The International Context, Rutgers University Press, 2007, p. 41; and then by Jean Dubuffet in 1946 in his Notes pour les fins-lettrés, the first text of which is ‘Partant de l’informe’; the writer Georges Bataille uses it as early as 1929 in his Dictionnaire critique.

[xiii] For the exhibition ‘Véhémences confrontées’.

[xiv] Mathieu, Au-delà du tachisme, p. 61.

[xv] Mathieu’s only solo exhibition prior to that of the René Drouin Gallery was at the Dutilleux bookshop in Douai in 1942. The Mathieu–Looten duo will be shown again by Tapié in Lille in April 1953 at the Marcel Évrard Gallery.

[xvi] In an avant-garde page make-up that Mathieu will continue to use for a decade in the review United States Lines Paris Review, which he will found in 1953.

[xvii] Underlined in the text.

[xviii] Mathieu, Au-delà du tachisme, p. 208.

[xix] Who operated the liner America on the Le Havre–New York line.

[xx] Mathieu confirms that he was ‘the first to mention them to Estienne, to Jaguer, to Guilly, to Tapié ’ (Mathieu, Au-delà du tachisme, p. 59).

[xxi] With works by Bryen, de Kooning, Gorky, Hartung, Mathieu, Picabia, Pollock, Reinhardt, Rothko, Russell, Sauer, Tobey, and Wols.

[xxii] ‘Mathieu pressed them [Charles Egan, Julien Levy, and Betty Parsons] but obtained only a few, unimpressive works on paper’ (Catherine Dossin, The Rise and Fall of American Art, 1940–1980, Ashgate, 2015, p. 61).

[xxiii] In particular, thanks to the loan by the American artist Alfonso Ossorio of works on canvas by Pollock and de Kooning from his own collection.

[xxiv] Cf. Michel Tapié, Un art autre, Gabriel-Giraud et fils, 1952.

[xxv] The ancestor of The Paris Review.

[xxvi] Georges Mathieu, ‘Portrait of the Critic ’, Paris News Post, June 1951.

[xxvii] Whose name in full is Georges Victor Adolphe Mathieu d’Escaudœuvres.

[xxviii] Letter of 10 January 1951, Michel Tapié archives, Kandinsky Library, Paris, quoted by Juliette Evezard for the exhibition catalogue L’Aventure de Michel Tapié, Un art autre, Luxembourg, 2016.

[xxix] Cf. Georges Mathieu, Au-delà du tachisme, p. 73.

[xxx] 2 by 4 metres, currently in the collections of the Pompidou Centre / MNAM, Paris.

[xxxi] Kristine Stiles, Peinture, photographie, performance: Le cas de Georges Mathieu, catalogue of the Mathieu retrospective at the Jeu de Paume, 2003, p. 77.

[xxxii] Frédérique Villemur and Brigitte Pietrzak, Paul Facchetti, le Studio, art informel et abstraction lyrique, Actes Sud, 2004, p. 27.

[xxxiii] By Stuart Preston 9 November 1952, cf. Daniel Abadie, in Georges Mathieu, exhibition catalogue for the Mathieu retrospective at the Jeu de Paume, 2003, p. 263.

[xxxiv] Subtitled ‘Where it is a matter of new unwindings of the real’, and in which the epigraph by André Malraux seems to place it under his intellectual authority.

[xxxv] Tapié, Un art autre.

[xxxvi] Which makes him the artist most represented in the book.

[xxxvii] Mathieu, Au-delà du tachisme, p. 81.

[xxxviii] Currently in the collections of the Pompidou Centre / MNAM, Paris.

[xxxix] In the same section as the article Pollock Paints a Painting appeared in May 1951.

[xl] Xavier Girard, interview with Jean Larcade, ‘Jean Larcade, la galerie Rive Droite’, Art Press, July 1988, p. 33.

[xli] 2.95 m × 6 m, currently in the collections of the Pompidou Centre / MNAM, Paris.

[xlii] Xavier Girard, ‘Jean Larcade, la galerie Rive Droite ’, p. 34.

[xliii] Now housed in the Pompidou Centre.

[xliv] Cf. Daniel Abadie, Georges Mathieu, p. 264.

[xlv] Georges Mathieu, Cinquante ans de création, Hervas, 2003, p. 56.

[xlvi] Mathieu, Au-delà du tachisme, p. 97.

[xlvii] Published by George Wittenborn à New York.

[xlviii] The American painter Paul Jenkins had held his first solo exhibition at the Studio Facchetti in 1954.

[xlix] Originally published in English.

[l] Marcel Cohen and Rodolphe Stadler, Galerie Stadler, trente ans de rencontres, de recherches, de partis pris, 1955–1985, Galerie Stadler, 1985, p. 6.

[li] Cf. Thomas R. H. Havens, Radicals and Realists in the Japanese Nonverbal Arts: The Avant-garde Rejection of Modernism, University of Hawaii Press, 2006, p. 93.

[lii] Cf. Shoichi Hirai, ‘Paris et l’art japonais depuis la guerre – Réflexions autour des tendances des années cinquante’ in Paris du monde entier. Artistes étrangers à Paris 1900-2005, exhibition catalogue, Tokyo: Asahi Shimbun, Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 2007.

[liii] Cf. Havens, Radicals and Realists in the Japanese Nonverbal Arts, p. 94.

[liv] 具体 which, made up of the ideograms signifying ‘tool’ and ‘body ’, means ‘concrete’ in Japanese.

[lv] Cf. Ming Tiampo, Gutai – Decentering Modernism, University of Chicago Press, 2011, p. 91.

[lvi] Jirō Yoshihara, Gutai bijutsu sengen, Geijutsu Shinchō, December 1956.

[lvii] Cf. Éric Mézil, ‘Nul n’est prophète en son pays’, “le cas de Michel Tapié” ’, in: Gutaï, exhibition catalogue, Paris, Ed. du Jeu de Paume, 1999, p. 30–31.

[lviii] Georges Mathieu, Cinquante ans de création, Hervas, 2003, p. 63.

[lix] Also entitled Bataille de Kōan, this being the second battle of Hakata Bay, in 1281.

[lx] Mathieu, Cinquante ans de création, p. 63.

[lxi] This being the first battle of Hakata Bay, in 1274.

[lxii] Founder of the school of floral art Ikebana Sōgetsu.

[lxiii] Who will become in 1959 the first director of the Tokyo National Museum of Western Art, cf. Réna Kano, edited by Didier Schulmann, ‘Georges Mathieu, Voyage et peintures au Japon, août-septembre 1957’, dissertation, 2009; he will declare that Mathieu is ‘the greatest French painter since Picasso ’ (Patrick Grainville and Gérard Xuriguera, Mathieu, Nouvelles Éditions Françaises, 1993).

[lxiv] The most widely read Japanese daily.

[lxv] Georges Mathieu, Cinquante ans de création, p. 63; a work also called Hideyoshi Toyotomi.

[lxvi] Georges Mathieu, Au-delà du tachisme, p. 129.

[lxvii] Cf. Kano, ‘Georges Mathieu, Voyage et peintures au Japon’, 2009.

[lxviii] Also in order to welcome Sam Francis, who arrives on 20 September for his exhibition.

[lxix] Kōichi Kawasaki, Le Séjour de Georges Mathieu au Japon, catalogue for the Mathieu retrospective at the Jeu de Paume, 2003, p. 95.

[lxx] To use the expression of Pierre Guéguen, Aujourd’hui, no. 6, 1956.

[lxxi] Cf. Frederick Gross, Mathieu Paints a Painting, City University of New York, 2002.

[lxxii] Which was defended by an efficient network of influence and assisted by fragmentation and a lack of consensus in France and in Europe, cf. Serge Guilbaut, ‘Disdain for the Stain: Abstract Expressionism and Tachisme ’, in Abstract Expressionism, The International Context, Rutgers University Press, 2007, p. 39.