Nahmad Contemporary and Perrotin are delighted to present a booth dedicated to lyrical abstraction’s founder Georges Mathieu. Considered one of the most influential postwar French artists, this presentation will bring together a selection of rare works from the ’60s/’70s and marks the return of the artist in the United Kingdom after a long time. Amongst the works are L’écartèlement de François Ravaillac, assassin du roi de France Henri IV, le 27 mai 1610, à Paris en place de Grève (1960, left on the picture), The Battle of Gilboa (La Bataille de Gilboa, 1962, right on the picture) and Hommage à Robert le Pieux (1958).

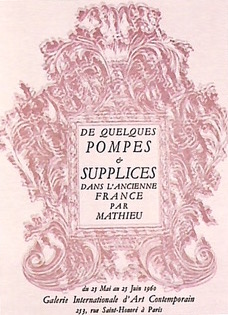

One of the highlights of the booth, L’écartèlement de Ravaillac, 1960 was first created for the exhibition “Pompes et Supplices dans l’ancienne France” at the Galerie Internationale d’Art Contemporain in Paris in May 1960. On this occasion, John Ashbery, the American art critic and poet, wrote in the New York Herald Tribune: “The new paintings of Georges Mathieu on view at the Galerie Internationale are among the finest work he has done so far, and probably establish him as France’s foremost abstract painter. (…) The new work has a richness, a completeness, a truth which cannot be ignored, and for the first time, perhaps, it has that kind of unquestionable authority that Jackson Pollocks’s best work has. It should convince all but the most stubborn foes of abstract painting”.

One of the highlights of the booth, L’écartèlement de Ravaillac, 1960 was first created for the exhibition “Pompes et Supplices dans l’ancienne France” at the Galerie Internationale d’Art Contemporain in Paris in May 1960. On this occasion, John Ashbery, the American art critic and poet, wrote in the New York Herald Tribune: “The new paintings of Georges Mathieu on view at the Galerie Internationale are among the finest work he has done so far, and probably establish him as France’s foremost abstract painter. (…) The new work has a richness, a completeness, a truth which cannot be ignored, and for the first time, perhaps, it has that kind of unquestionable authority that Jackson Pollocks’s best work has. It should convince all but the most stubborn foes of abstract painting”.

Georges Mathieu was fascinated by history; the titles of his works often pay homage to myths. Here the title refers to François Ravaillac, a madman who murdered Henri the IV, King of France, in 1610 and was sentenced to death by quartering. This large painting (250 x 400 cm) belongs to the Pompes & Supplices series, at once festive and funeral, like an exaltation of life and death. Here the artist combines a spontaneous gesture to a precise technique, resulting into an organized anarchy of signs and creating a great balance between centripetal and centrifugal forces within the painting.

This major and monumental work surprisingly prefigures the developments that would take place five years later, in the mid-sixties, in Mathieu’s painting, with the rigour of certain forms, just as it prefigures the paintings of the eighties with its unprecedented vehemence.

The gaze is immediately drawn to a green line, a color very rarely used by Mathieu because at first glance it evokes nature, which has no place in abstract painting. But its meaning is quite different here. In one of his books, Mathieu quotes Vincent Van Gogh “who said that green and red are the symbols of human passions“, and these are the two chromatic colors of this painting. We can therefore understand the emotional charge of this green flash that scars the canvas in its centre, its evocation of a great pain. Art critic Nicole Duault lingers on this central element:

This green line that zigzags over a glowing red composition, full of whitish scratches, is of a merciless intensity. A shock. A break.

L’Écartèlement de Ravaillac offers us the rare privilege of being in closest contact with a “violent, indignant Mathieu, moved by the blood spilt” as the art critic Jean-Louis Ferrier points out. Patrick Grainville, of the Académie Française, writes: “L’écartèlement de Ravaillac invokes dripping until saturation, until bloody flood.”

Another highlight of the booth, The Battle of Gilboa (La Bataille de Gilboa, 1962), was painted for Mathieu’s exhibition in Jerusalem. Mathieu refers to the Battle of Mount Gilboa (circa 1050 BC) between the Israelite and the Philistine armies, which was a turning point in Israel’s political history. King Saul died during this famous battle, while David, the soon to be king of Israel, was away fighting the Amalekites. Georges Mathieu stayed in Jerusalem for 10 days and painted there 18 artworks for the show. The Battle of Gilboa was painted in public. As Dr. Haim Gamzu, then Director of the Tel Aviv Museum, wrote: “(the artwork was) painted in front of a large audience, at the Bezalel Museum, within a few hours. Mathieu (…) appears on the spot, all by himself, swiftly glancing, peering into the deep recessed of his own, and grabbing his paints tubes, his hand gyrating a dazzling acrobatic reel, like a devout dervish wheeling to attrition up to the pic of ecstasy.” Georges Mathieu was very interested in visiting Israel and was very impressed by the mysticism of the country.

Other works on the booth refers to historical episodes, such as Hommage à Robert le Pieux, 1958 or Morienval, 1965 once again testifying of Mathieu’s erudition and fascination for history. Works from the ’70s and ’80s will also be on view, showing the evolution of Mathieu’s oeuvre to a more refined style.